Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center

Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center

AG History

History in the Making: The Heritage of the Assemblies of God

Video Introduction to Assemblies of God History (2008 Version)

History in the Making highlights the modern-day Pentecostal revival and the formation of the Assemblies of God in 1914. The video was originally produced in 1999 as an orientation piece for tours of the Assemblies of God national office. It has been edited for local church use and features updated music, narration, and graphics. History in the Making is an excellent tool for understanding and sharing the history of the Assemblies of God and is useful for membership classes and other church education needs. (Updated: 2008 / Length: 8 minutes 50 seconds)

History in the Making is available for free download: MP4 video (zip file)

Fully Committed: 100 Years of the Assemblies of God

By Darrin J. Rodgers

The article was published in the centennial edition of Assemblies of God Heritage magazine.

Citation: Darrin J. Rodgers, “Fully Committed: 100 Years of the Assemblies of God,” Assemblies of God Heritage 34 (2014): 4-15.

Founding Chairman E. N. Bell, in a December 1914 article titled, “General Council Purposes,” declared that “our first aim and supreme prayer” is to focus on the spiritual life. “Let us keep to the front,” he wrote, “deep spirituality in our souls and the power and anointing of God on our ministry.”1

The men and women who pioneered the Assemblies of God desired — more than anything else — to be fully committed to Christ and His mission. These pioneers included young people and veteran preachers, visionaries and faithful plodders, and housewives and laborers.

They were unified by a common experience of the Word and Spirit which brought them close to God and propelled them to be witnesses to the world. They were on a mission to share the love of Jesus in word and deed. They preached the gospel, prayed for the sick, witnessed miracles, published profound insights on the spiritual life, and established churches, schools, orphanages, and rescue missions.

Some of these pioneers founded churches that flourished and became large. Others captured newspaper headlines with high profile revivals. However, most labored in relative obscurity, pouring all available time and resources into ministry in their local communities. Together these saints laid the foundation for the Assemblies of God.

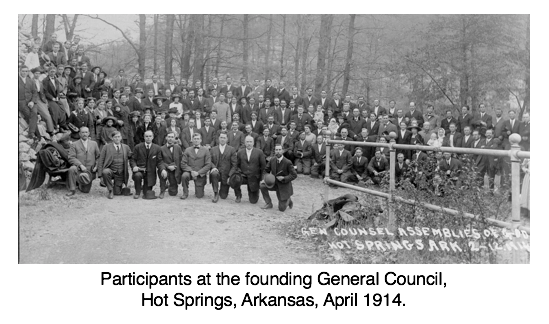

The Assemblies of God was organized in April 1914, in Hot Springs, Arkansas, in order to provide accountability, structure, and unity so that Pentecostals could better carry out the mission of God in their communities and around the world. This vision transcended the racial and social divides, and the Assemblies of God grew to become a multi-ethnic and international movement. The approximately 300 men and women who came together in Hot Springs organized a fellowship that in 100 years would become one of the largest families of Christian churches in the world.

The Assemblies of God was organized in April 1914, in Hot Springs, Arkansas, in order to provide accountability, structure, and unity so that Pentecostals could better carry out the mission of God in their communities and around the world. This vision transcended the racial and social divides, and the Assemblies of God grew to become a multi-ethnic and international movement. The approximately 300 men and women who came together in Hot Springs organized a fellowship that in 100 years would become one of the largest families of Christian churches in the world.

Their story is our story.

Early Pentecostal Revival

The Assemblies of God is one of several denominations birthed in the early twentieth-century Pentecostal revival. Early Pentecostals embraced a worldview that, at its heart, emphasized a transformative encounter with God.

Pentecostals drew from a tapestry of beliefs within evangelicalism. Like other evangelicals, they had a high view of scripture. Like other Holiness believers, they aimed for full consecration — which included separation from sin and a desire to be fully committed to Christ and His mission. Many adopted the Wesleyan doctrine of entire sanctification — the idea that the believer’s desires could be reshaped by the Holy Spirit to become perfect in love. Others embraced the Reformed emphasis on Spirit baptism for empowerment for Christian service. Most Pentecostals affirmed classic premillennial eschatology, which predicted a period of rapid social decay, followed by Christ’s return. And Pentecostals became some of the most prominent participants in the faith healing movement.

While Pentecostals drew from many theological streams within evangelicalism, they formed an identifiable movement because of their common commitment to the experience of baptism in the Holy Spirit. This emphasis on a post-conversion experience of Spirit-baptism was widespread within certain segments of evangelicalism in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Why did the doctrine and experience of the baptism in the Holy Spirit become attractive to large numbers of people? Because it addressed one of their most basic spiritual longings — a desire to be close to God. Many believers were captivated by the desire for a deeper life in Christ; they were spiritually hungry and desired to be more committed Christ-followers. These ardent seekers saw in Scripture that Spirit baptism provided empowerment to live above normal human existence; this transformative encounter with God brought believers into closer communion with God and empowered them to witness.

While many sought Spirit baptism, uncertainty existed regarding how to determine whether one had received it. Answering this question, Kansas Holiness evangelist Charles F. Parham identified a scriptural pattern — that the “Bible evidence” (later called the “initial evidence”) of Spirit baptism was speaking in tongues.

Students at his Bible school in Topeka, Kansas, began speaking in tongues at a prayer meeting on January 1, 1901. Through his Apostolic Faith movement located in the south central states, Parham had some success in promoting the gift of tongues.

The 1906 revival at the Apostolic Faith Mission on Azusa Street in Los Angeles catapulted the young movement before a larger audience. William Seymour, an African-American and former student of Parham, led the Azusa Street mission. The revival lasted for three years, reportedly with non-stop services, day and night.

This revival brought together men and women from diverse religious, ethnic and national backgrounds. Participant Frank Bartleman famously exulted that at Azusa Street “[t]he ‘color line’ was washed away in the blood.”2 Scores of periodicals — from around the world and in numerous languages — carried reports of this revival.

As news of the outpouring spread, ministers and lay persons made pilgrimages to Azusa Street to experience the remarkable revival and to seek to be baptized in the Holy Spirit. Participants became known as Pentecostals, named after the Jewish feast of Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit was first given to the church, and believers first spoke in tongues (Acts 2). It is important to note that Pentecostals viewed tongues as the evidence — and not the purpose — of Spirit baptism. The purpose is to glorify Christ. William Seymour admonished people at the Azusa Street Mission, “Now, don’t go from this meeting and talk about tongues, but try to get people saved.”3

While much ink has been spilled about the Topeka and Azusa Street revivals, they were neither the first nor the only such revivals. The earliest Pentecostals recounted similar revivals in the late 1800s and early 1900s across the world, and throughout church history.4 Early AG educator Henry H. Ness declared, “During the 19 centuries since Christ whenever the spiritual life has run high, during revivals, the Lord has baptized with the Holy Ghost as He did on the Day of Pentecost.”5

Formation of the Assemblies of God

Many established churches did not welcome this revival, and participants felt the need to form new congregations. As the revival rapidly spread, many Pentecostals recognized the need for greater organization and accountability. The founding fathers and mothers of the Assemblies of God met in Hot Springs, Arkansas on April 2-12, 1914, to promote unity and doctrinal stability, establish legal standing, coordinate the mission enterprise, and establish a ministerial training school. The business meeting was called “General Council” and the new body was called the General Council of the Assemblies of God.

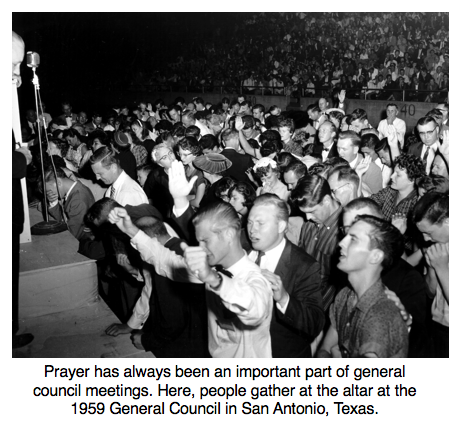

It was a momentous occasion. Walter Higgins later recalled a “halo of glory that rested over the sessions from day to day…. God saw fit to bless this meeting with a visitation of His Holy Ghost. The praises rose from those gathered in the service, seemingly like a mighty sea.”6

Participants at the first General Council represented a variety of independent churches and networks of churches, including the Association of Christian Assemblies in Indiana  and a group identified as the “Church of God in Christ and in Unity with the Apostolic Faith Movement” from Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Texas. This latter group originated with Parham and, despite its name, appears to have been structurally separate from Bishop Charles H. Mason’s largely African-American denomination, the Church of God in Christ.7

and a group identified as the “Church of God in Christ and in Unity with the Apostolic Faith Movement” from Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Texas. This latter group originated with Parham and, despite its name, appears to have been structurally separate from Bishop Charles H. Mason’s largely African-American denomination, the Church of God in Christ.7

Bishop Mason was one of the speakers at the first General Council and blessed the formation of the Assemblies of God.8 He also brought the black gospel choir from the Church of God in Christ school in Lexington, Mississippi, which sang at the first General Council. It was significant, given the “Jim Crow” laws of the day, that Mason and the founders of the Assemblies of God were willing to cross the color line.9

The exact nature of the relationship of Mason to the founders of the Assemblies of God is unknown. At minimum, they knew and respected each other. It is possible that a formal relationship existed between the two organizations, but this has not been demonstrated due to a lack of historical documentation.10

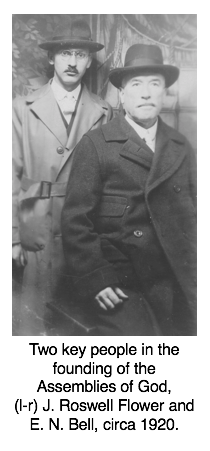

The approximately 300 participants at the Hot Springs meeting incorporated the General Council with a hybrid congregational and presbyterian polity. The first two officers elected were Eudorus N. Bell as chairman (title later changed to general superintendent) and J. Roswell Flower as secretary. While most other U.S. Pentecostal denominations were regionally defined, the Assemblies of God claimed a broad nationwide constituency.

Doctrine

The Assemblies of God, like other Classical Pentecostals, identified with the broader Holiness movement, which melded evangelical doctrine with an emphasis on the need for a deeper spiritual life. Salvation and sanctification were primary concerns.

The Assemblies of God did not adopt a formal theological statement at its first general council, intentionally allowing for some theological diversity within the bounds of the Holiness worldview. The preamble to the first constitution of the Assemblies of God aimed for unity despite differences: “endeavoring to keep the unity of the Spirit in the bonds of peace, until we all come into the unity of the faith.”11

One of the first major divisions within Pentecostalism pertained to the issue of sanctification. Some held to a radical Wesleyan view that it is possible for the sin nature to be eradicated following an instantaneous experience of sanctification. Many who disagreed advocated a more traditional Wesleyan view (termed “Finished Work”), contending that sanctification is progressive, not instantaneous, and that perfection is not possible on earth. Most Assemblies of God founders adhered to the latter “Finished Work” view.12

Assemblies of God leaders quickly realized the need to develop theological boundaries. Almost immediately, they were faced with a new teaching that denied the doctrine of the Trinity. This new teaching (called the “New Issue” or Oneness theology) was sweeping through the Pentecostal movement, and a large number of Assemblies of God ministers had embraced it. In 1916 the General Council approved a Statement of Fundamental Truths, which affirmed the Fellowship’s Trinitarian and evangelical witness. This resulted in the departure of Oneness advocates, as well as those who opposed what was perceived as “creedalism.”

Assemblies of God leaders quickly realized the need to develop theological boundaries. Almost immediately, they were faced with a new teaching that denied the doctrine of the Trinity. This new teaching (called the “New Issue” or Oneness theology) was sweeping through the Pentecostal movement, and a large number of Assemblies of God ministers had embraced it. In 1916 the General Council approved a Statement of Fundamental Truths, which affirmed the Fellowship’s Trinitarian and evangelical witness. This resulted in the departure of Oneness advocates, as well as those who opposed what was perceived as “creedalism.”

Organizational Development

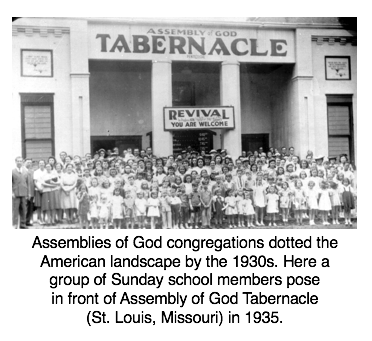

Initially, the primary function of the Assemblies of God headquarters was to publish literature through its Gospel Publishing House. As the responsibilities for its home and overseas efforts grew increasingly complex, it established the Missionary Department in 1919 and the Home Missions and Education Department in 1937. Other departments followed (e.g., Youth, Sunday School, Missionettes, Royal Rangers). First located in Findlay, Ohio, the headquarters moved to St. Louis in 1915, and finally to Springfield, Missouri, in 1918.

The Assemblies of God adopted two official periodicals: the monthly Word and Witness and the weekly Christian Evangel. These two periodicals merged in 1916; the resulting weekly periodical was renamed the Pentecostal Evangel in 1919. The Evangel, one of the largest-circulation Pentecostal papers in the world, networked far-flung believers and helped to unite the Fellowship.

Education

From the outset, the Assemblies of God promoted the development of educational institutions. The fifth purpose of the “Call to Hot Springs” was “to lay before the body for a General Bible Training School with a literary department for our people.” The phrase “literary department” was used in the 19th and early 20th centuries and roughly corresponds to a “liberal arts school” today. The Assemblies of God was formed, in part, to encourage both ministerial training and liberal arts education.13

Initially, the Assemblies of God endorsed several small regional Bible institutes. Some survived to become enduring institutions; others merged or closed. The Assemblies of God chartered its first national school, Midwest Bible School, Auburn, Nebraska, which opened in 1920 and closed the next year. The second attempt at a national school was successful: Central Bible Institute, later Central Bible College, was formed in Springfield, Missouri, in 1922. Two additional national residential schools were established in Springfield: Evangel College (1955), later Evangel University, a school of arts and sciences; and the Assemblies of God Graduate School (1973), later Assemblies of God Theological Seminary. These three Springfield schools consolidated under the name Evangel University in 2013.

Additional permanent institutions have included: Vanguard University of Southern California (1920) in Costa Mesa; Latin American Bible Institute (1926) in La Puente, California; Latin American Bible Institute (1926) in San Antonio, Texas; and Southwestern Assemblies of God University (1927) in Waxahachie, Texas; North Central University (1930) in Minneapolis, Minnesota; Southeastern University (1935) in Lakeland, Florida; Valley Forge Christian College (1939) in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania; Trinity Bible College (1948) in Ellendale, North Dakota; American Indian College (1957) in Phoenix, Arizona; Caribbean Theological College (1959) in Bayamon, Puerto Rico; Western Bible College (1967) in Phoenix, Arizona; Native American Bible College (1968) in Shannon, North Carolina. Northpoint Bible College in Haverhill, Massachusetts, formerly Zion Bible College, was founded as an independent school in 1924 and received endorsement by the AG in 2000. Bethany University (founded 1919) had been the oldest continuing Assemblies of God school until it closed its doors in 2011.

Additional permanent institutions have included: Vanguard University of Southern California (1920) in Costa Mesa; Latin American Bible Institute (1926) in La Puente, California; Latin American Bible Institute (1926) in San Antonio, Texas; and Southwestern Assemblies of God University (1927) in Waxahachie, Texas; North Central University (1930) in Minneapolis, Minnesota; Southeastern University (1935) in Lakeland, Florida; Valley Forge Christian College (1939) in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania; Trinity Bible College (1948) in Ellendale, North Dakota; American Indian College (1957) in Phoenix, Arizona; Caribbean Theological College (1959) in Bayamon, Puerto Rico; Western Bible College (1967) in Phoenix, Arizona; Native American Bible College (1968) in Shannon, North Carolina. Northpoint Bible College in Haverhill, Massachusetts, formerly Zion Bible College, was founded as an independent school in 1924 and received endorsement by the AG in 2000. Bethany University (founded 1919) had been the oldest continuing Assemblies of God school until it closed its doors in 2011.

Global University (resulting from a merger of the stateside Berean School of the Bible and the overseas International Correspondence Institute) provides accredited distance education programs for those seeking training for various forms of Christian ministry. Sixteen nationally endorsed schools of higher education, ranging from Bible institutes to colleges and universities, could be found across the United States by 2014. Hundreds of smaller Bible institutes, sponsored by churches and districts, also exist.

Missions

World missions has always been central to the identity of the Assemblies of God. Delegates at the second General Council, held in Chicago in November 1914, resolved to achieve “the greatest evangelism that the world has ever seen.”14 By 1915 the Assemblies of God endorsed approximately thirty missionaries. They operated in independent fashion and primarily worked in the traditional sites of Christian mission: Africa, India, China, Japan, and the Middle East; others later served in Europe, Latin America, and Oceania.

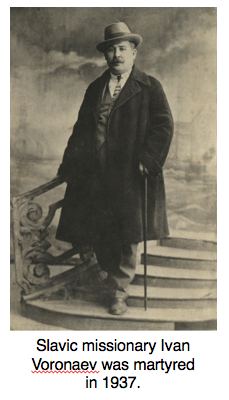

Some of the greatest heroes in the Assemblies of God have given up everything, including their own lives, to serve as missionaries in hostile environments. Ivan Voronaev, the Assemblies of God missionary who went to Russia and the Ukraine in 1920, helped to organize approximately 500 Slavic churches. He was arrested by Soviet authorities in 1930 and was thrown into Siberian prison camps. Voronaev’s plight was covered by the Evangel, and American believers kept him in their prayers. Soviet authorities demanded money for his release. The AG paid, but Voronaev was not released and was instead martyred in prison in 1937.15 J. W. Tucker, a missionary to the Congo, also lost his life for the gospel. He was beaten to death by rebels in 1964, and his story was captured by his widow in a book, He is in Heaven.16 Voronaev, Tucker, and a host of other missionaries helped inspire Assemblies of God members to participate in missions through giving and personal service.

At first, the Missionary Department’s primary functions were to endorse missionaries and channel funds from donors to the missionaries. Beginning in 1943 it began to aggressively direct the strategy of the mission enterprise.

At first, the Missionary Department’s primary functions were to endorse missionaries and channel funds from donors to the missionaries. Beginning in 1943 it began to aggressively direct the strategy of the mission enterprise.

The Assemblies of God committed itself in 1921 to a missions strategy of establishing self-governing, self-supporting and self-sustaining churches in missions lands. Alice E. Luce, a Spirit-baptized Anglican missionary to India who transferred to the Assemblies of God in 1915, influenced the Assemblies of God to adopt this indigenous church principle long before it was embraced by most mainline Protestant groups. The policy was not uniformly implemented, and some Assemblies of God missionaries continued to follow the paternalistic practices of other Western churches during the early decades of the twentieth century.

Beginning in the 1950s Assemblies of God missionaries placed greater emphasis on training indigenous leaders. This change from paternalism to partnership brought dramatic church growth in many nations. Missions leaders such as Ralph D. Williams, J. Philip Hogan, and Melvin L. Hodges helped to implement this indigenous strategy, resulting in the development of hundreds of ministerial training institutions around the world.

The 1968 General Council reaffirmed its threefold reason for being — an agency for the evangelization of the world, a corporate body in which humanity may worship God, and a means for the discipleship of Christians. Despite the failure to address issues related to holistic mission (e.g., poverty, hunger), Assemblies of God missions, already holistic in many quarters, increasingly moved in that direction without diminishing gospel proclamation. Such ministries included the Lillian Trasher Orphanage in Assiout, Egypt; the Mission of Mercy Hospital and Research Centre in Kolkata, India; HealthCare Ministries; and the Assemblies of God-related Convoy of Hope. The 2009 General Council added compassion as the fourth element for its reason for being, making explicit what had long been implicit. In 2013, the Assemblies of God USA reported 2,750 missionaries and associates around the world. When missionaries sent by other national fellowships are also taken into account, the global cooperative witness of the Assemblies of God is far-reaching.

In 2013, the World Assemblies of God Fellowship reported over 67 million adherents. The Assemblies of God has become one of the largest Protestant families of churches in the world. This incredible growth, according to J. Philip Hogan, resulted not just from strategy, but from reliance on the Holy Spirit: “The essential optimism of Christianity is that the Holy Spirit is a force capable of bursting into the hardest paganism, discomfiting the most rigid dogmatism, electrifying the most suffocating organization, and bringing the glory of Pentecost.”17

National Ministries

The Assemblies of God was formed, in large part, to aid ministry in the local church. Over the years, national ministries have been developed to meet the needs of people from cradle to grave. National ministries for children and youth were pioneered in the 1920s, starting with graded Sunday school curriculum and an organization for youth and young adults — Christ’s Ambassadors (C.A.’s).

New ministries were begun in the mid twentieth century, including Speed the Light (1944), Boys and Girls Missionary Challenge (1949), Chi Alpha (1953), Light for the Lost (1953), Missionettes (1956, now National Girls Ministries), Royal Rangers (1962), Teen Bible Quiz (1962, now Bible Quiz), and Fine Arts (1963). The Revivaltime radio broadcast, a 30-minute weekly program, was launched in 1950 with Wesley Steelberg as speaker. The next two speakers, who broadcast on the ABC radio network, C. M. Ward (1953-1978) and Dan Betzer (1979-1995), became two of the best-known personalities in the Assemblies of God. Not only did these and other national ministries help evangelize and disciple believers, they also gave the Assemblies of God a sense of national identity or branding.

These programs have provided formative experiences for generations of Assemblies of God young people. Assemblies of God educator Billie Davis was raised as a hobo kid in a poor migrant worker’s family. She credited Sunday school for her life achievements: “As a child I received hope and courage, a serene attitude toward hardships, and a kindly indulgent attitude toward human beings from my experiences in Sunday school. I found in the philosophy and religion of Jesus Christ a way to live without bitterness, which in the hobo jungles among the cursing, embittered campers who lived raw lives and tried to ease their pain by blaming others, was little short of a miracle in itself.”18

Ethnic Diversity

While the 300 ministers at the founding General Council in Hot Springs were mostly white, the Assemblies of God soon expanded across the ethnic divides. At least two of the founding members were Native American. William H. Boyles and Watt Walker, both Cherokees from Oklahoma, were at the Hot Springs meeting. The Assemblies of God ordained its first known Hispanic minister in 1914 (Antonio Ríos Morin) and its first African-American in 1915 (Ellsworth S. Thomas). It created a conference for Hispanic churches in the US in 1918 (later known as the Latin American District).

Its first African-American missionaries were Isaac and Martha Neeley, who were ordained as missionaries to Liberia in 1913 by the largely-white “Church of God in Christ and in Unity with the Apostolic Faith Movement.” When that group disbanded in 1914, the Neeleys did not officially transfer their credentials to the newly-formed Assemblies of God. The Neeleys remained in Liberia for four or five years and received support from churches that had joined the Assemblies of God, most notably the Stone Church in Chicago. They returned to America and received Assemblies of God credentials as evangelists in 1920. In 1923, they were appointed to serve as Assemblies of God missionaries to Liberia, effective 1924. Isaac died in December 1923, and Martha went on to Liberia alone.19

The German Branch was formed in 1922, and in the 1940s and 1950s eight additional language branches were formed, mostly for Europeans who had settled in the United States. By the 1970s, most of these language branches for European immigrants had dissolved after their members had Americanized. In 1973 language branches were renamed districts. Since the 1980s, new language districts have been formed for new immigrants (Korean, Brazilian, Slavic, and Samoan). Fellowships have been formed for 21 additional ethnic groups.20

The German Branch was formed in 1922, and in the 1940s and 1950s eight additional language branches were formed, mostly for Europeans who had settled in the United States. By the 1970s, most of these language branches for European immigrants had dissolved after their members had Americanized. In 1973 language branches were renamed districts. Since the 1980s, new language districts have been formed for new immigrants (Korean, Brazilian, Slavic, and Samoan). Fellowships have been formed for 21 additional ethnic groups.20

Despite the Assemblies of God’s early interracial character and its roots in the interracial Azusa Street revival, the racial tensions in the broader culture found their way into the Fellowship. Some white leaders showed paternalism to Hispanics and people from other cultural backgrounds. But the most blatant example of racism was the adoption in 1939 of a policy that denied ordination at the national level to African-Americans. This policy was neither widely publicized nor consistently applied.21

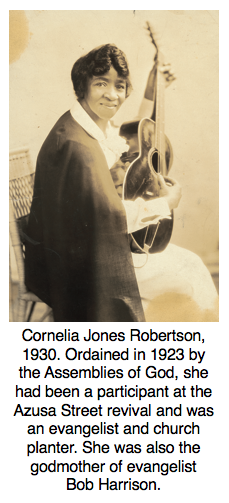

Bob Harrison, a talented African-American associate of Billy Graham, was the catalyst for the policy to be rescinded in 1962. Harrison went on to become a prominent Assemblies of God evangelist and missionary. He encouraged believers of different races to unite in ministry: “May Christians of all colors join together to bring the victory. For the enemy is not the white man or the black man but the devil himself. Let us together be more than conquerors for Christ."22

Significant efforts to repent of racism and to be racially inclusive have been made in recent decades. The 1989 General Council adopted a resolution opposing “the sin of racism in any form,” calling for repentance from anyone who may have participated in racism “through personal thought or action, or through church or social structures.”23 The 1995 General Council resolved to encourage the “inclusion of black brothers and sisters throughout every aspect of the Assemblies of God.”24 In 1997, the General Council voted to include representatives of ethnic fellowships in the General Presbytery and Executive Presbytery. In a groundbreaking election, an African-American Executive Presbyter, Zollie Smith, was elected in 2007 to serve as executive director of U.S. Missions.

In recent years, the non-white constituency in the Assemblies of God has exploded in growth, while the number of whites has plateaued. The percentage of adherents who were white decreased from 68.6% in 2003 to 58.7% in 2013. The Assemblies of God continues to show strong numerical growth, particularly when compared to other major denominations, largely because of growth among ethnic minorities.

Women in Ministry

Continuing in the tradition of the Holiness movement, women played important roles in early Pentecostalism and the Assemblies of God as evangelists, missionaries, and pastors. Originally offering them ordination only as evangelists and missionaries, the General Council began ordaining women as pastors in 1935. However, many women served in the role of pastor prior to 1935 without corresponding denominational recognition. For these women, God’s call trumped the lack of an official ecclesiastical endorsement. The Pentecostal affirmation of women in ministry was a radical application of the Protestant ideal of the priesthood of all believers.

Before 1950 more than one thousand women evangelists had traveled the country evangelizing and planting churches. Influential women included Zelma Argue, Marie Burgess Brown, Etta Calhoun, Alice Reynolds Flower, Hattie Hammond, Chonita Howard, Alice E. Luce, Aimee Semple McPherson (in the Assemblies of God from 1919 to 1922), Carrie Judd Montgomery, Louise Nankivell, Florence Steidel, Lillian Trasher, Louise Jeter Walker, Alta Washburn, and Mildred Whitney.

While these female ministers were ahead of their time, their ministry arose from their devotional lives and not from a modern social ideology. Ministry doors opened because of their deep spiritual lives. Hattie Hammond was well-known for encouraging believers to seek a deeper life in Jesus Christ: “I believe we should wait before the Lord until we realize we are in the presence of God, until every thought has been brought into captivity, and we are lifted above the world and shut in with God as though there were no other in the world but just the Lord Jesus and ourself."25

By mid-century, however, the number of women credential holders fell into a sharp decline. This decline resulted from numerous factors. Some churches, for instance, adopted theological and cultural attitudes that did not support spiritual leadership by females. One of the most significant reasons for the decline in female ministers, perhaps, was a diminishing demand for the types of ministry that women typically filled. Most early women ministers were not pastors of established congregations, but entrepreneurs who launched into ministry on their own as evangelists or church planters. By mid-twentieth century, some Assemblies of God leaders tried to protect established churches from perceived competition by discouraging new church plants in the same city or region. This policy helped existing churches, which tended to favor male pastors. This trend reversed in recent decades; the percentage of women ministers in the Assemblies of God has increased from 14.9% in 1990 to 22.3% in 2013. The number of female senior pastors increased from 400 in 2000 to 529 in 2012, although some of these lead non-AG churches. Contributing to this turnaround are a cultural shift in attitudes toward women in ministry, the support of denominational leaders, and a renewed emphasis in church planting.

Cooperation

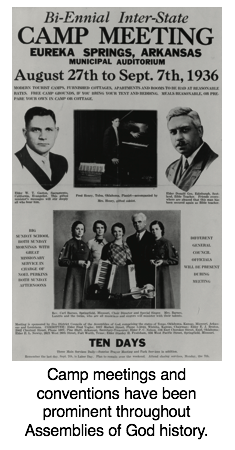

Early Pentecostals often cooperated at the local level in city-wide evangelistic crusades and similar campaigns. They crossed the racial, denominational, and social divides in practical ministry endeavors. This was true in early tent meetings 100 years ago, at the salvation-healing campaigns of the 1950s, and in the charismatic renewal from the 1960s through the 1980s.

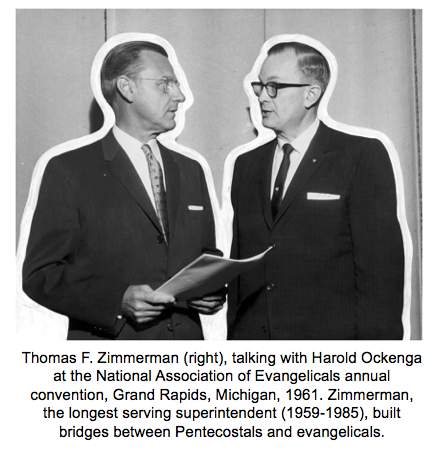

The Assemblies of God was a leader in several new organizations, formed in the 1940s, that brought evangelicals and Pentecostals together. The Assemblies of God was a founding member of the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) in 1942. The NAE established a national evangelical voice on issues such as religious liberty and also encouraged cooperation on world evangelization. NAE membership helped the Assemblies of God to be identified with the broader evangelical movement and removed the cult status with which some observers had labeled it. More than any other Pentecostal, Thomas F. Zimmerman, Assemblies of God General Superintendent (1959-1985), worked to build bridges between evangelicals and Pentecostals.

The Assemblies of God was also a founding member of the Pentecostal World Conference (1947) and the Pentecostal Fellowship of North America (1948) and cooperated with the Lausanne Committee on Evangelism, the World Evangelical Alliance, and the Wesleyan Holiness Consortium.

The Assemblies of God was also a founding member of the Pentecostal World Conference (1947) and the Pentecostal Fellowship of North America (1948) and cooperated with the Lausanne Committee on Evangelism, the World Evangelical Alliance, and the Wesleyan Holiness Consortium.

Pentecostals have tended to be suspicious of the kind of ecumenism practiced by many mainline churches, which they have viewed as compromising doctrine and ethics for the sake of organizational unity. Therefore, the Assemblies of God has refrained from involvement in conciliar bodies such as the National Council of Churches and the World Council of Churches.

New Revival Movements

A hunger for more of God — desiring to be fully committed to Christ and His mission — is part of the spiritual DNA of the Assemblies of God. The Assemblies of God was birthed in the midst of the early twentieth century Pentecostal revival. Assemblies of God pioneers prayed for fresh outpourings of God’s spirit in years to come. In 1938, Andrew H. Argue wrote, “We are in a movement that is still young. It is full of young people. It is a live movement because it was brought into existence by contending for the faith, and it will only remain alive while we continue to contend for the faith."26

New revival movements have sprung up in the past 100 years, bringing both encouragement and challenges. One of the new revival movements, dubbed the “New Order of the Latter Rain,” arose among Pentecostals at the Sharon Schools and Orphanage, in North Battleford, Saskatchewan, Canada in 1948. Latter Rain proponents, like early Pentecostals, believed they were restoring all of the gifts of the Holy Spirit to the New Testament church. However, those involved in the Latter Rain movement began to alienate other Pentecostals.

Some Latter Rain proponents advocated an extreme form of congregationalism, which in practice resulted in a lack of accountability. This also led to some self-proclaimed apostles and prophets with poor morals and questionable doctrines bringing disrepute on the movement. Most Pentecostal denominations, including the Assemblies of God, condemned these excesses. While the movement did not result in a denominational division, some leaders and congregations withdrew from the Assemblies of God.

At the same time another movement, which emphasized salvation and healing, started in the late 1940s. This salvation and healing movement included many prominent evangelists, such as A. A. Allen, W. V. Grant, and Jack Coe, who started out in the Assemblies of God but ultimately formed independent ministries. One of the troubling legacies of the movement was the establishment of a large network of powerful independent evangelists who had little accountability.

Salvation and healing evangelists attracted the attention of many non-Pentecostals, which resulted in Pentecostal revival breaking out in the 1950s where Pentecostals least expected — mainline churches. This revival, which became known as the charismatic renewal, created some confusion among Pentecostals, who were uncertain how to react.

Pentecostals often suspected the new charismatics would leave their old churches for Pentecostal churches, but many charismatics stayed put. Latter Rain leaders also retooled their doctrines for charismatic audiences. Latter Rain emphases re-emerged during the charismatic renewal in various forms, including demonology, the discipleship movement, positive confession theology, and an interest in modern-day apostles and prophets.

Pentecostals and charismatics sized each other up, coming together in numerous prayer groups, conferences, and preaching events. Assemblies of God leaders offered a measured response to the charismatic renewal in 1972:

“The winds of the Spirit are blowing freely outside the normally recognized Pentecostal body.… The Assemblies of God does not place approval on that which is manifestly not scriptural in doctrine or conduct. But neither do we categorically condemn everything that does not totally … conform to our standards.… It is important to find our way in a sound scriptural path, avoiding the extremes of an ecumenism that compromises scriptural principles and an exclusivism that excludes true Christians.”27

New revival movements, such as the “Pensacola Outpouring” at the Brownsville Assembly of God (Pensacola, Florida) that attracted more than 2.5 million visitors after it began in 1995, spiritually invigorated many Assemblies of God people.

The Future

In its centennial year, the Assemblies of God shows strong signs of progress and also faces significant challenges. In the past decade, the Assemblies of God has placed renewed emphasis on church planting, as well as on education, missions, and better inclusion of women and ethnic minorities in church leadership. The Assemblies of God consistently shows growth that is much higher than most other large Christian denominations in the United States. With over 3.1 million adherents in 2013, the Assemblies of God was the ninth-largest denomination in the United States.

There is a danger, however, that these encouraging statistics will breed a sense of triumphalism. The believers who make up the Assemblies of God are to be commended for bringing millions to faith in Christ and for faithfully working to fulfill the Great Commission. However, Pentecostal history reveals a more complex story — one in which testimonies of saved lives, restored families, and healed bodies are accompanied by stories of human frailty, sacrifice, and struggle.

Most revival movements in Christian history lost their fire after several generations, leaving behind institutions with faded memories of the spiritual passion that birthed them. Will the Assemblies of God retain its Pentecostal identity? Will it continue to encourage people to be fully committed to Christ and His mission?

Pentecostals began the twentieth century as a small, marginalized group at odds with the broader society. By the end of the century, large segments within Pentecostalism had adapted to the cultural mores of American society. Success used to be measured in terms of purity, but now many Pentecostals reject separation from the world as legalism.

What is the future of the Assemblies of God? In 1953, W. T. Gaston, former General Superintendent (1925-1929), suggested, “If we are to have a future that is better or even comparable and worthy of our past, we will need to learn over again some of the lessons of yesterday.”28 One of the important lessons to rediscover, he wrote, was the importance of promoting “pure, undefiled” religion.

What is the future of the Assemblies of God? In 1953, W. T. Gaston, former General Superintendent (1925-1929), suggested, “If we are to have a future that is better or even comparable and worthy of our past, we will need to learn over again some of the lessons of yesterday.”28 One of the important lessons to rediscover, he wrote, was the importance of promoting “pure, undefiled” religion.

According to Gaston, history’s “tragic lesson” is that a church’s solid foundation does not prevent corruption from “fleshly elements within.” He offered this warning at a time when certain media-savvy Pentecostal healing evangelists had been exposed for their ungodly lifestyles, but who continued to promote their unbiblical message that God guarantees financial prosperity.

Gaston recalled the “utter disregard for poverty or wealth or station in life” that he witnessed in the early Pentecostal movement: “Completely satisfied without the world’s glittering tinsel, and content to be the objects of its scornful hatred, those rugged pioneers had something that made them attractive and convincing.”

Gaston’s observations should provoke current Assemblies of God members to do some soul-searching. I pray that our Pentecostal priority remains on the spiritual life — which is lived out in purity of heart and power for witness. If younger Pentecostals heed this lesson from older Pentecostals, the future of the Assemblies of God will be in good hands.

About the Author

Darrin J. Rodgers, M.A., J.D., is director of the Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center and editor of Assemblies of God Heritage magazine.

Endnotes:

- E. N. Bell, “General Council Purposes,” Christian Evangel, December 19, 1914, 1.

- Frank Bartleman, How Pentecost Came to Los Angeles (Los Angeles, CA: the author, 1925), 54.

- B. F. Lawrence, The Apostolic Faith Restored (St. Louis, MO: Gospel Publishing House, 1916), 86.

- B. F. Lawrence, The Apostolic Faith Restored (St. Louis, MO: Gospel Publishing House, 1916); Stanley Howard Frodsham, With Signs Following, rev. ed. (Springfield, MO: Gospel Publishing House, 1946).

- Henry H. Ness, Demonstration of the Holy Spirit as Revealed by the Scriptures and Confirmed in Great Revivals (Seattle: Hollywood Temple, [1940s?]), 5.

- Walter J. Higgins, as told to Dalton E. Webber, Pioneering in Pentecost: My Experiences of 46 Years in the Ministry (Bostonia, CA: the author, 1958), 42.

- Darrin J. Rodgers, “The Assemblies of God and the Long Journey Toward Racial Reconciliation,” Assemblies of God Heritage 28 (2008): 54-58.

- “Hot Springs Assembly; God’s Glory Present,” Word and Witness 10:4 (April 20, 1914): 1.

- Ithiel C. Clemmons, Bishop C. H. Mason and the Roots of the Church of God in Christ (Bakersfield, CA: Pneuma Life Publishing, 1996), 71.

- Rodgers, 54-58

- General Council Minutes, April 1914, 4.

- Bruce E. Rosdahl, “The Doctrine of Sanctification in the Assemblies of God”( Ph.D. thesis, Dallas Theological Seminary, 2008). Rosdahl contends that the “Finished Work” view of sanctification is both Wesleyan and non-eradicationist and is sometimes mischaracterized as Reformed or Baptistic.

- Darrin J. Rodgers, “Historical Rationale for Training Ministers Alongside Laypersons in Schools Owned by the General Council of the Assemblies of God,” unpublished paper, 2011. FPHC.

- General Council Minutes, November 1914, 12.

- Dony K. Donev, “Ivan Voronaev: Slavic Pentecostal Pioneer and Martyr,” Assemblies of God Heritage 30 (2010): 50-57.

- Angeline Tucker, He is in Heaven (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965).

- J. Philip Hogan, “The Spirit is Moving over the World,” Pentecostal Evangel, May 21, 1972, 13.

- Sylvia Lee, “Billie Davis: Voice for Education and Appreciation,” Assemblies of God Heritage 19:2 (Summer 1999): 6.

- Isaac and Martha Neeley, ministerial and missionary files. FPHC.

- William Molenaar, “Intercultural Ministries,” in U.S. Missions: Celebrating 75 Years of Ministry (Springfield, MO: Gospel Publishing House, 2012), 52-69. Molenaar includes a chart of ethnic/language branches, districts, and fellowships.

- Rodgers, “The Assemblies of God,” 50-61.

- Bob Harrison with Jim Montgomery, When God Was Black (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1971), 159.

- General Council Minutes, 1989, 117-118.

- General Council Minutes, 1995, 72-74.

- Hattie Hammond, “Drawing Nigh to God,” Pentecostal Evangel, August 18, 1928, 6.

- A. H. Argue, “When God Sent the Latter Rain,” Pentecostal Evangel, March 19, 1938, 3.

- “Charismatic Study Report,” Advance, November 1972, 3.

- W.T. Gaston, "Guarding our Priceless Heritage," Pentecostal Evangel, August 16, 1953, 3-4, 11.

General Superintendents of the Assemblies of God USA

Eudorus N. Bell

Arch P. Collins

John W. Welch

William T. Gaston

Ernest S. Williams

Wesley R. Steelberg

Gayle F. Lewis

Ralph M. Riggs

Thomas F. Zimmerman

G. Raymond Carlson

Thomas E. Trask

George O. Wood